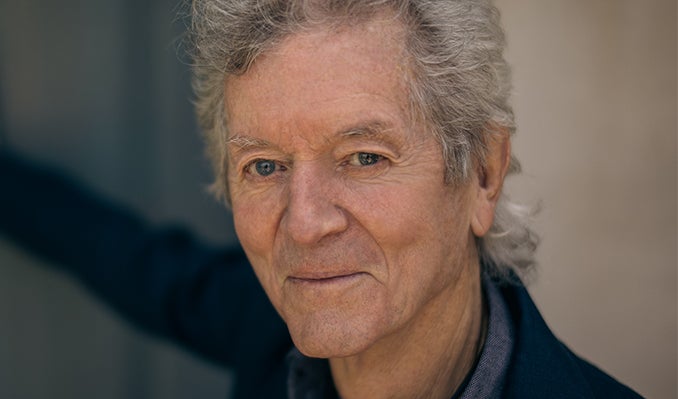

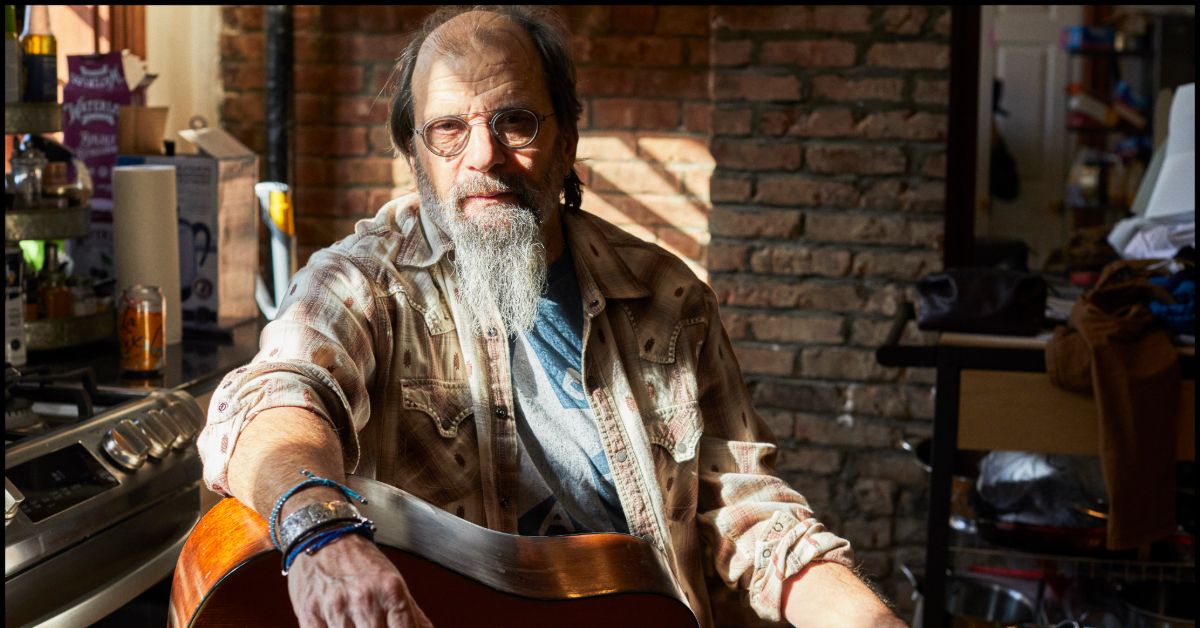

Steve Earle

Artist Information

Steve Earle is one of the most acclaimed singer-songwriters of his generation. A protege of legendary songwriters Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark, he quickly became a master storyteller in his own right, with his songs being recorded by Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, Joan Baez, Emmylou Harris, The Pretenders, and countless others. 1986 saw the release of his record, Guitar Town, which shot to number one on the country charts and is now regarded as a classic of the Americana genre.

Most recently, Earle’s 1988 hit Copperhead Road was made an official state song of Tennessee in 2023. Subsequent releases like The Revolution Starts...Now (2004), Washington Square Serenade (2007), and TOWNES (2009) received consecutive GRAMMY® Awards. His most recent album, Jerry Jeff (2022) consisted of Earle’s versions of songs written by Jerry Jeff Walker, one of his mentors.

Earle has published both a novel I’ll Never Get Out Of This World Alive (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt 2011) and Dog House Roses, a collection of short stories (Houghton Mifflin 2003). Earle produced albums for other artists such as Joan Baez (Day After Tomorrow)and Lucinda Williams (Car Wheels On A Gravel Road)

As an actor, Earle has appeared in several films and had recurring roles in the HBO series The Wire and Tremé. In 2017, Earle appeared in the off-Broadway play Samara, for which he also wrote a score that The New York Times described as “exquisitely subliminal.” Earle wrote music for and appeared in Coal Country, for which he was nominated for a Drama Desk Award. Earle is the host of the weekly show Hard Core Troubadour on Sirius Radio’s Outlaw Country channel.

In 2020, Earle was inducted into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame. And in 2023, Steve was honored by the Bruce Springsteen Archives & Center for American Music. On September 17, 2025, Steve Earle made Opry history as the first artist inducted during our milestone 100th year.

Upcoming Performances

Grand Ole Opry: OPRY 100

Featuring Lauren Alaina, T. Graham Brown, Steve Earle, Charles Esten, Skip Ewing, Nashville Irish Step Dancers, Chonda Pierce, Sunny Sweeney, and Gene Watson.

Similar Artists

Stay In Touch

It's our biggest year yet! Don't miss any Opry 100 announcements, events, and exclusive offers for fans like you. Sign up now!